Johann Schwarz and his contribution to Freemasonry

Some of our latest news

Johann Schwarz and his contribution to Freemasonry

One of the key figures of the Enlightenment in the Russian Empire was Johann Georg Schwarz (1751-1784), a teacher, publisher, philosopher and one of the most influential Freemasons of his time. Little is known about his origins. He was presumably born in 1751 in Transylvania and studied at the University of Jena in the early 1770s. In 1776, at the invitation of Prince Nikolai Trubetskoy, he arrived in Moscow, where he was initiated into Freemasonry. In the same year, Schwarz visited Mitau (modern Jelgava in Latvia), where he met with local Freemasons. It is important to note that until 1795 Mitau was part of the Duchy of Courland and Semigallia, which was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In the second half of the 18th century, Mitau was one of the most important educational and cultural centres in the territory of modern Latvia. It was the main residence of the Dukes of Courland, and in 1779 the city became famous because of the arrival of Alessandro Cagliostro, the famous adventurer and Freemason.

Being one of the most educated figures of the Enlightenment, Schwarz became a professor at Moscow University in the philosophy department in 1779. Around the same time, he met Nikolai Novikov. They were united by their mutual desire to bring Russian and Western Freemasonry closer together by introducing additional mystical degrees, the purpose of which was self-contemplation through in-depth study of mysticism and additional rituals.

In 1780 Schwarz, together with Nikolai Novikov, founded the "Harmony" lodge, which also included Semyon Gamaleya and other prominent Freemasons. In 1781 in Berlin, he was admitted to the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross, and in October of the same year received a charter for the right to be considered its sole authorised representative «in the entire Imperial Russian State and its lands».

Schwarz once again visited Mitau because of the Masonic task to establish contacts between Moscow Freemasons and the Rosicrucians. In Mitau he actively communicated with German Freemasons, reported on the state of Freemasonry in the Russian Empire and eventually received numerous letters of commendation recognising the independence of the Russian jurisdiction. Thanks to his activities in Mitau, Rosicrucian Freemasonry was firmly established in the Russian Empire. This once again emphasises the important role of the cities of modern Latvia in the history of Freemasonry.

After returning to Moscow, Schwarz became the Great Provincial Master of Russia in 1781, receiving recognition from Berlin and London. From this point onwards, he engaged in active pedagogical and philanthropic activities. Schwarz used his income to found the first pedagogical seminary in Moscow for the professional training of teachers, introducing the humanistic ideals of the Renaissance. He adhered to the model of classical Western education, based on the ideas of the Italian humanists and envisaged in-depth study of various disciplines along with ancient philosophy.

Schwarz attracted prominent Russian educators to the Order of the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross. This circle included: Nikolai Novikov, Semyon Gamaleya, the Trubetskoy family, Alexei Kutuzov, Ivan Lopukhin, Pyotr Turgenev, Mikhail Kheraskov and others.

In 1783, Schwarz, together with Novikov, created an independent chapter of Russian Freemasons.

Johann Schwarz's life in Moscow was extremely productive. For example, between 1782 and 1783 he gave private lectures on Freemasonry. Schwarz was a supporter of Martinism, a near-Masonic form of Christian mysticism, saturated with ancient and Hebrew ideas, which rejected the atheistic radicalism of the French revolutionaries.

He believed that human reason is a divine gift and a tool for knowing more about the world through science. However, he considered radical scepticism and rationalism harmful, arguing that total secularisation leads society to a decline. Like Plato, Schwarz believed that spiritual values are the guiding star of any society, as well as the guarantee of justice, law and morality.

Schwarz believed that Masonic philosophy could overcome any ideological radicalism and create the most harmonious society possible. He expressed his ideas in the journal "Evening Dawn", enlightening society through articles on ancient philosophy, Masonic and humanist ideals, and ways to achieve harmony between spirituality and reason. In his article "On Freethinkers and Unbelievers" Schwarz sharply condemned atheists, arguing that no society is capable of existing without higher spiritual ideals. Thus, the myth that Freemasonry is aimed at the destruction of religions and countries can be firmly dispelled. As the sources show, the Masonic enlighteners developed both spiritual values and science and did not consider religiosity and rationalism to be mutually exclusive.

In parallel with his work in the publishing house, Schwarz was involved in charity work, founding schools and providing money for teacher training. Unfortunately, in February 1784, he fell seriously ill and died at the age of 33, before he could fully realise his tasks related to educational activities in the Russian Empire. However, during his short life Schwarz did a lot for Freemasonry and society as a whole. Thanks largely to him, Russian Freemasonry formed its own identity and was recognised by Western lodges, which contributed to the formation of the Russian Empire as a European power capable of accepting Western humanistic and enlightenment ideas.

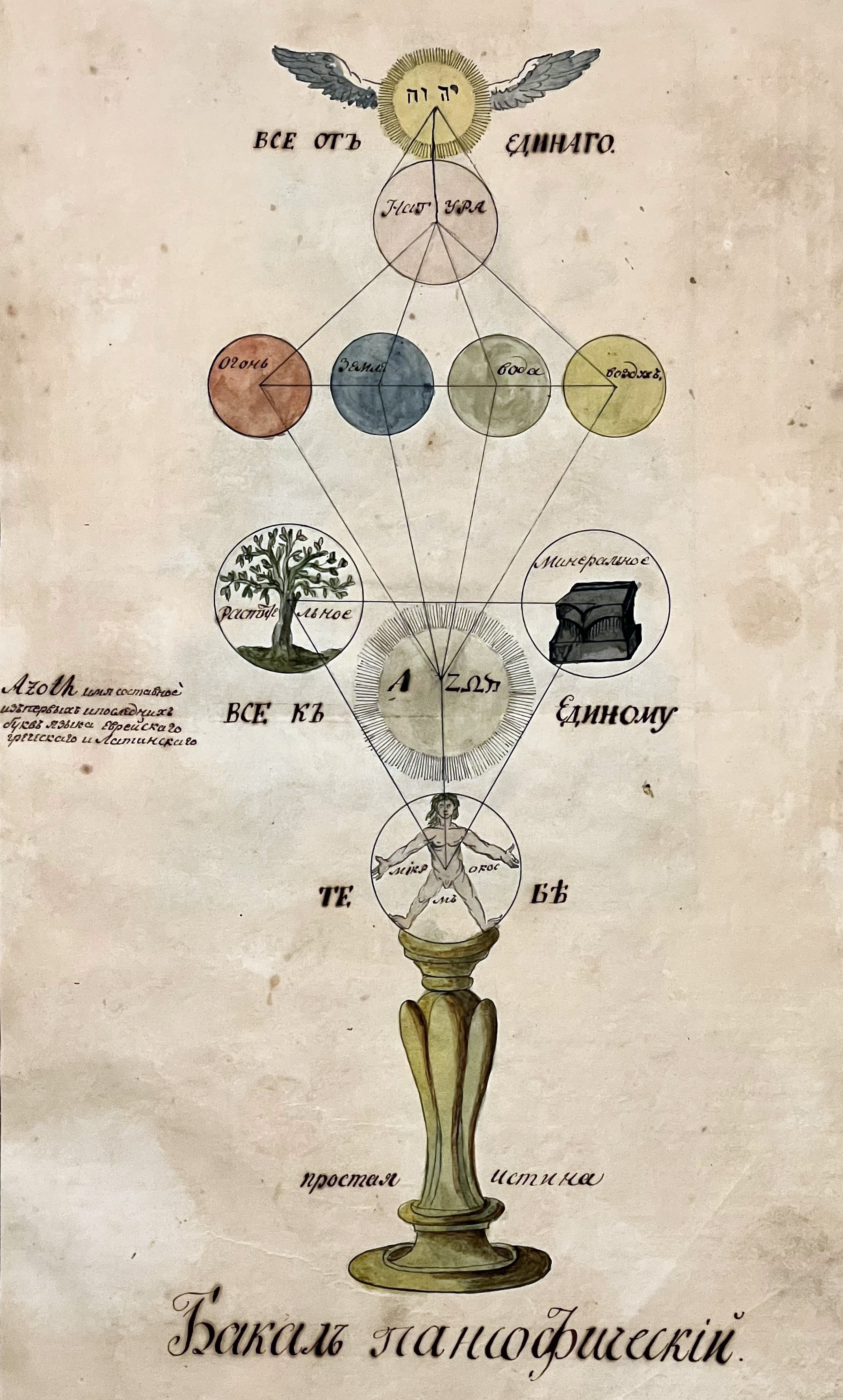

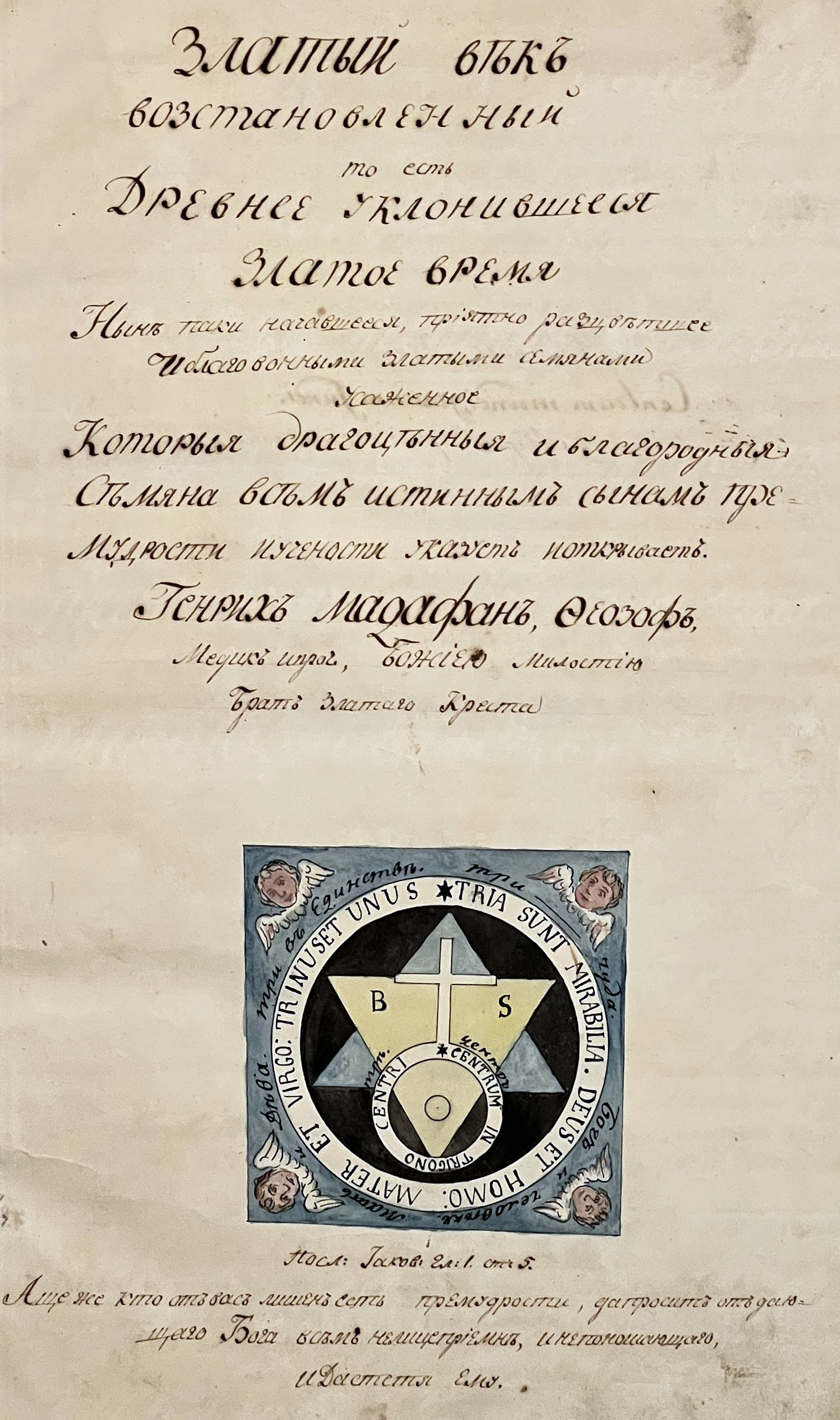

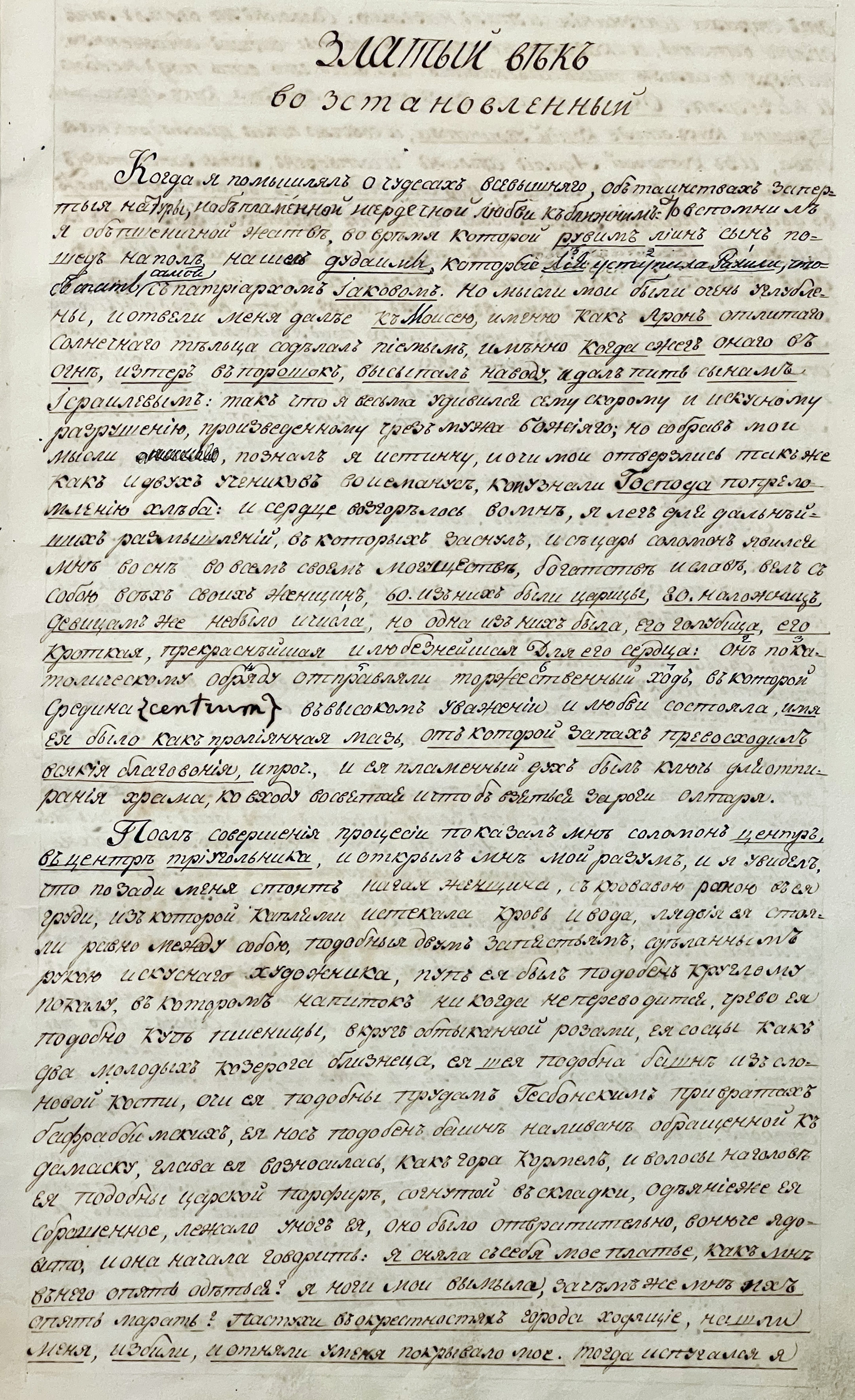

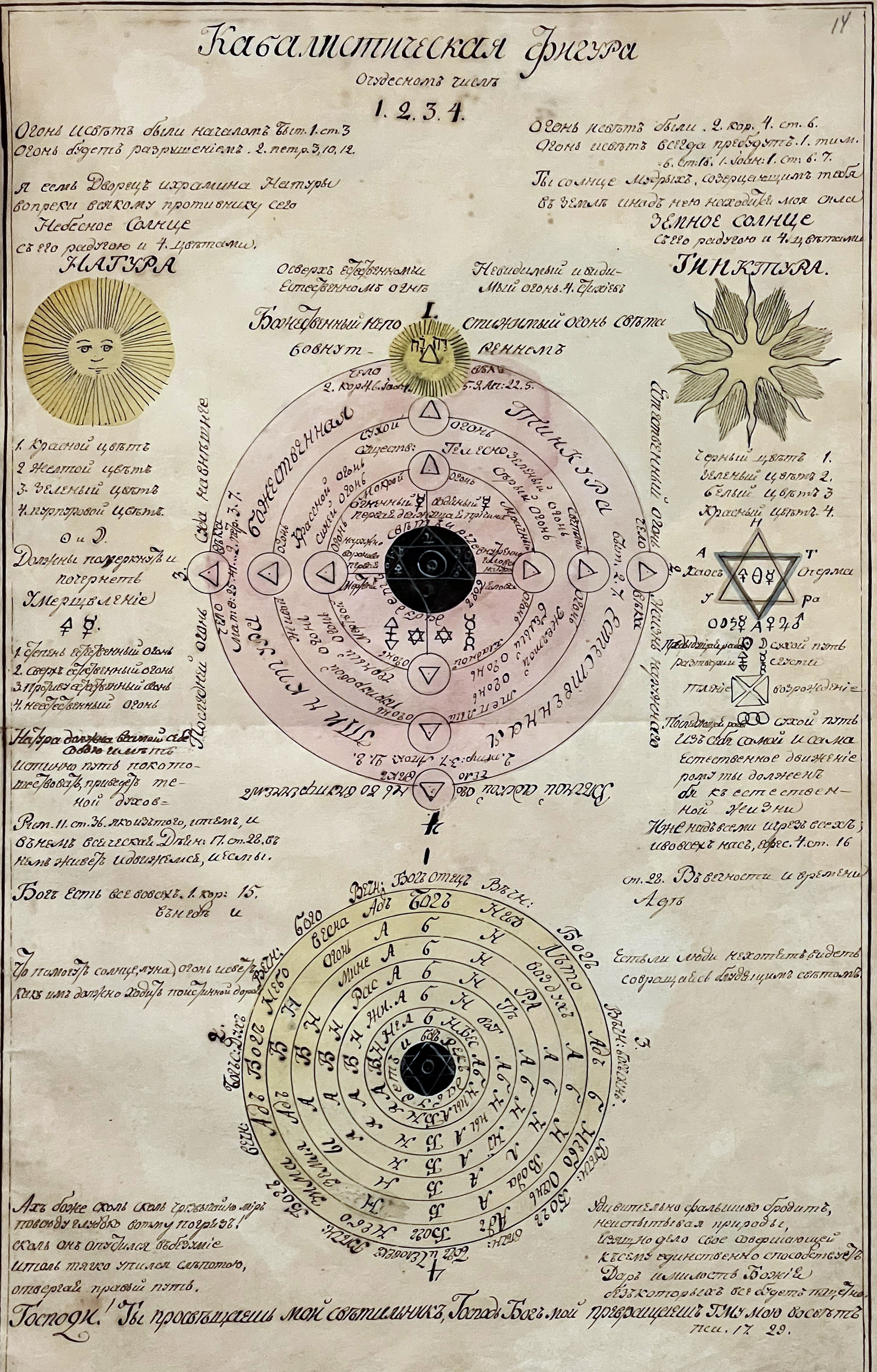

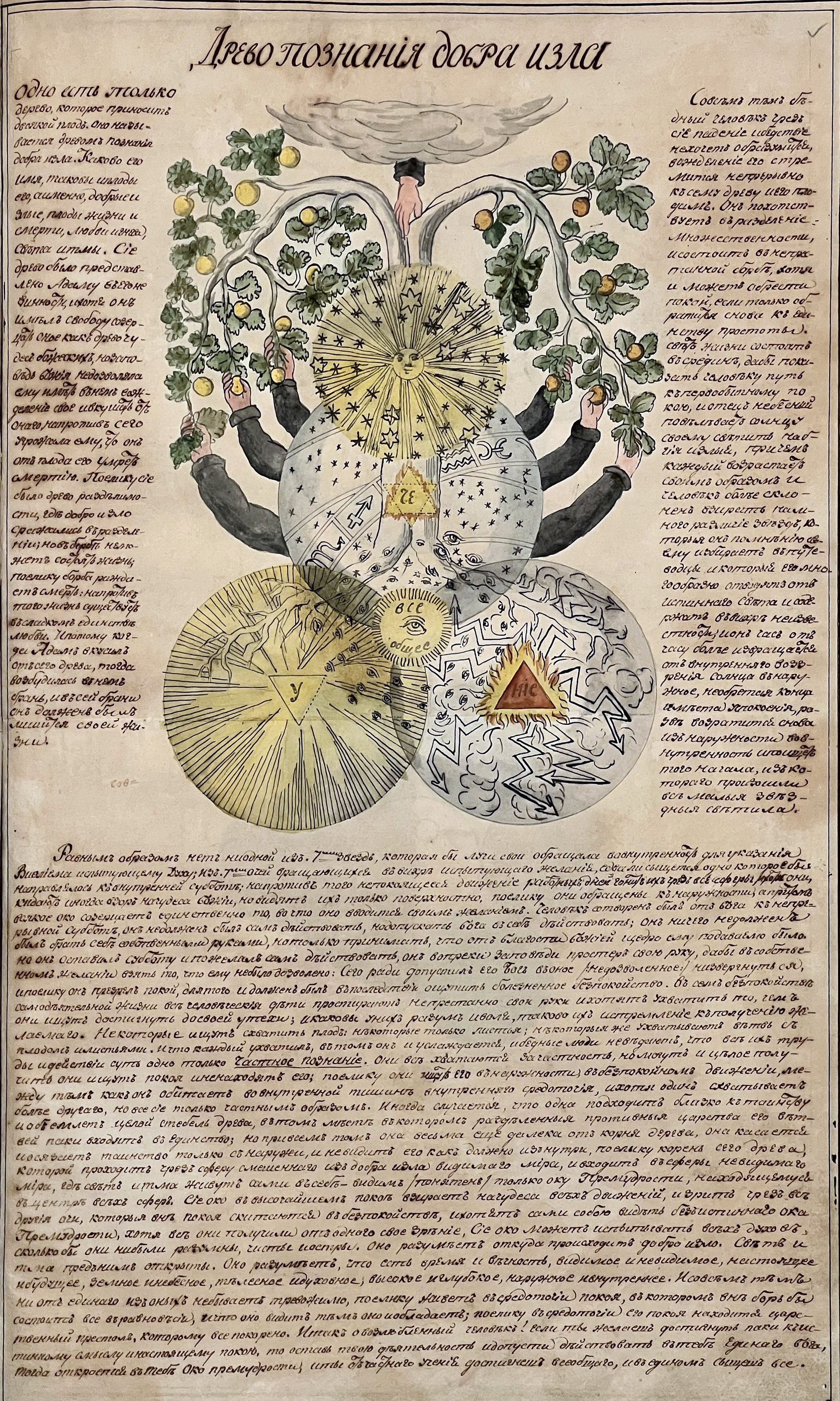

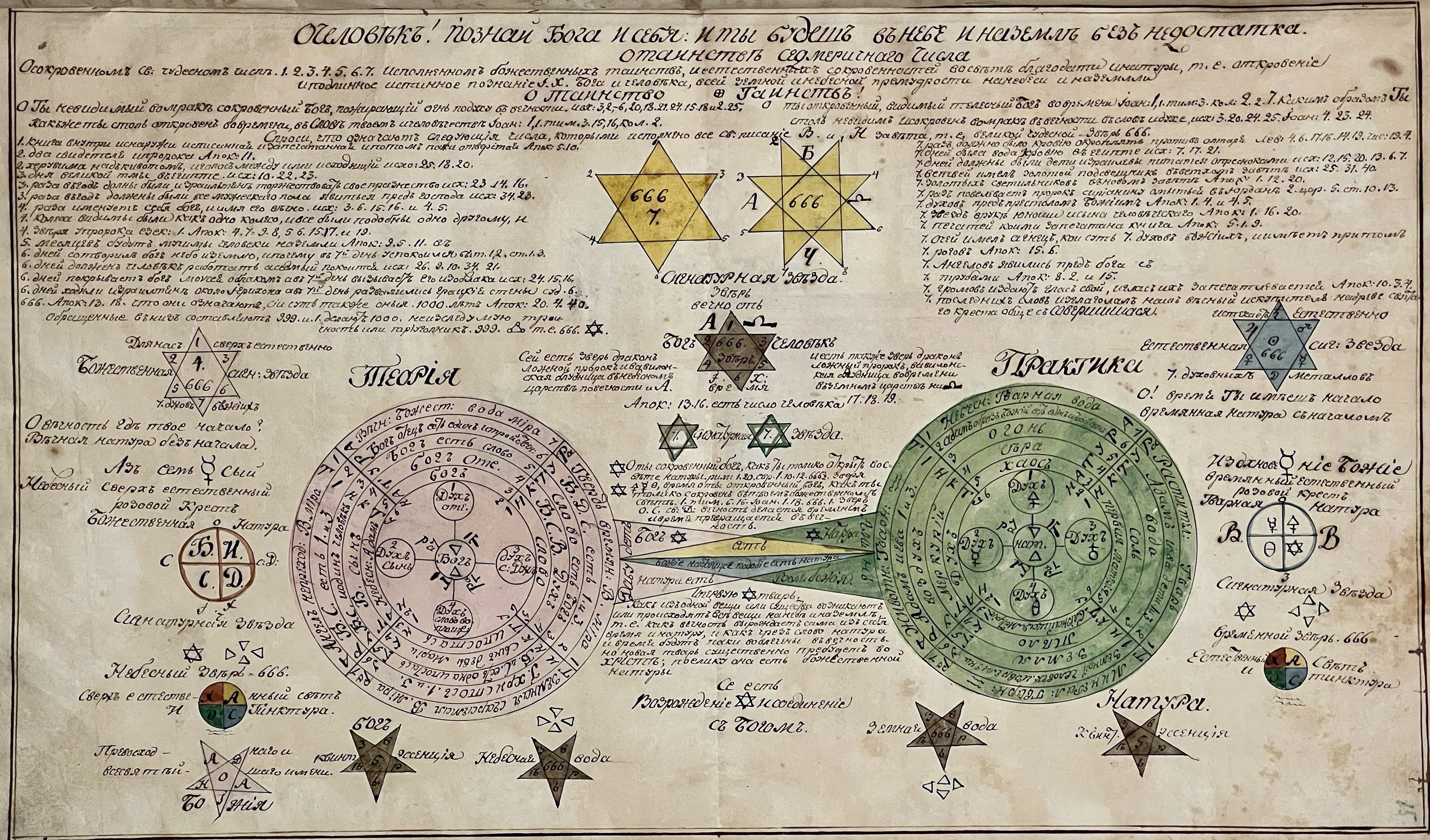

Illustration: In the collection of the Riga Museum of World Freemasonry there is a manuscript, presumably written by Semyon Gamaleya, relating to the basic knowledge of the Order of the Golden and Rosy Cross.

Museum

Museum