Tracing the Origins of Rumors about Orgies and Zoophilia

Some of our latest news

Tracing the Origins of Rumors about Orgies and Zoophilia

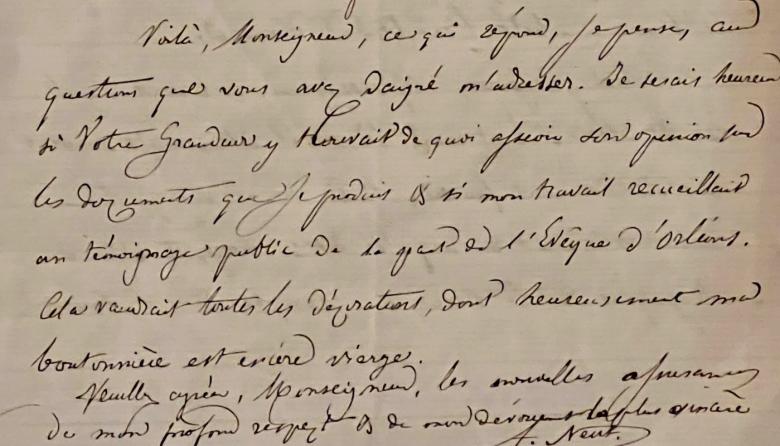

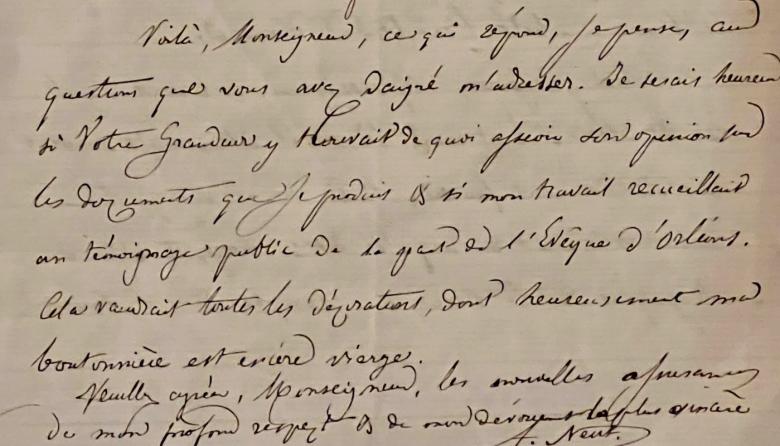

The collection of the Riga Museum of World Freemasonry has been enriched with a letter written in 1868 by Amand Neut, a renowned pro-Catholic publicist and anti-Masonry activist from Belgium, to the Bishop of Orleans, Felix Dupanloup. In the letter, Neut cites some theses from his own book - the two-volume Franc-Maçonnerie soumise au grand jour de la publicité à l'aide des documents authentiques - and refers to his articles published in Belgian newspapers. Particularly, the publicist talks about bestiality in Freemasonry and the order's struggle with the Catholic Church.

"I guarantee, monsignor, the accuracy of all the documents cited in my two volumes," writes the journalist. - I have the originals of some of them from the Belgian lodges." Neut complains to the bishop that he has repeatedly contacted various Masonic organizations, but has received no response to any of his inquiries. "I sent a copy of my work to several lodge-owned newspapers and received... a rejection? No.....absolute silence," he laments.

Yet Neut emphasizes that, unlike other critics of Freemasonry, he is responsibly checking the facts. The publicist cites as an example the text of his colleague M. De St Aubin, in which freemasons are accused of teaching each other debauchery and ties to prostitution, for which, according to Neut, there is no documentary evidence.

At the end of the letter, Neut asks Dupanloup for a review of the book. "I would be happy if my work could receive the public approval of the Bishop of Orléans," he writes

Neut was far from being alone in his views during those years. Bishop Dupanloup, to whom Amand Neut addresses his admiration and request to support his research, was a very famous preacher and writer, an ardent cleric, famous for his fight against female secular education in the 1870s in France.

In his complaints about the activities of the Masonic lodges, Dupanloup was not only indignant at the “widespread drunkenness” of the Masons and a tendency towards “ritual prostitution,” but also in a very biased fashion accused the “masons” of not building or producing anything at all: “As for the technical work of the Masons, then no one here has ever heard of them caring about this or doing any work at all. We know about their labors at the dinner table at fraternal meals; they pick up a pickaxe, set out cannons and barrels; and we also know that the Worshipful master holds a hammer in his hand and that the masters work sometimes on a rough cornerstone, sometimes on a cubic stone, but we have never seen any art object created by them, never heard that a freemason, a lodge or the Grand Orient have sent a work of art to a national or international exhibition, be it an architectural structure, sculpture, painting, engraving, etc.”(L'ALLOCUTION DE PIE IX ET LA MAÇONNERIE. Page 129)

Thanks to his love of moralizing, the bishop during his lifetime became the hero of more than a hundred popular satirical couplets with offensive content, sung to the tune of the song “Cadet Rousselle”. For example, these:

Père Dupanloup did it with the Sphinx

At night and from behind, however He said:

"She smiles so strange

Because she still doesn't know who that was!"

A characteristic feature of these couplets is that the main character in all situations solves the troubles that have arisen with the help of his genital organ and ultimately commits abominations and all sorts of obscenities, for which he invariably receives personal insults in the chorus section. Judging by the enormous popularity of the couplets among contemporaries, not everything was fictional, and in some places there was a rather sharp satire on the real life and activities of the bishop.

In actual fact, the whole story with the couplets is known to us first-hand thanks to historical evidence recorded in the work On Artists and Writers by Guillaume Apollinaire:

“Once, when a company of students was passing along the Rue Saint-André-des-Arts, singing the “Song about Father Dupanloup,” which is so simple that there is no way to quote it, Mr. Leek told me about the connection between the great prelate who glorified the Dupanloup family, and two of the most famous publishers of free-thinking and satirical works, the scientists Isidore Lizé and Alcide Bonneau,” says the writer’s book. “I don’t know if “Song about Father Dupanloup” was ever published, but almost everybody knows it. It inspired Mr. Jules Murray, by no means a popular novelist, to create a magnificent satirical collection entitled “The Exploits of Mr. Dupanloup”, a small book of poems that has already become or will undoubtedly become a rarity. In the preface the author writes:

“The French song, mocking and obscene, sparing neither the military nor the clergy, turned this prelate into a kind of Priapus or Christian Karagoz, endowing him with simply incredible reproductive power, making him a legend during his lifetime. The origins of the “Song about Father Dupanloup” most likely go back to the last years of the reign of Louis Philippe.

Monsieur Dupanloup (de pavone lupus), whom we alternately meet in a hot air balloon, in a train carriage, at the Institute, at the Opera and even - due to a simple-minded anachronism - while crossing the Berezina, was for almost half a century the object of a genuine erotic and patriotic cult of our soldiers, who sang about his exploits in order to be a little distracted during long marches and tiring maneuvers.”

A curious result of Monsignor Dupanloup’s pedagogical efforts!”

But, apparently, this prelate, who, however, was a holy man, possessed some kind of unhealthy power, of which it may not be possible to give another example. After all, his students at the seminary were Isidore Lisée and Alcide Bonneau, whose field of activity and application of erudition was most often literature, and the peculiar fame of their teacher expanded this field in the most unexpected way.”

The struggle of representatives of the Catholic Church with Freemasonry has a long history, which began during the Renaissance, when the predecessors of the Freemasons - Christian kabbalists-mystics and humanists - opposed Catholic dogmatists. This, in particular, led to the schism of the church in 1517 and marked the beginning of the Reformation. And soon after the public founding of the Grand Lodge of England in 1717, already a bull signed by Pope Clement XII was issued in 1738, concerning the incompatibility of the papal church and Freemasonry.

At the time of the events described in Neut’s letter to the Bishop of Orleans, the church was trying to completely subjugate even such neutral sphere as charity: by the mid-19th century, in almost all Catholic countries of Europe, this sphere was in the hands of Catholics. Fearing competition from Protestants and other religious movements, Catholics suppressed any initiatives of their religious opponents.

When the Grand Orient of Belgium was founded in 1833, philanthropy was seen as one of the ways through which Freemasonry could make the world a better place. One of the main lodges in the capital was called “Friends-Philanthropists”: Freemasons preferred to call themselves “philanthropists” rather than “charities.” In this way they emphasized that in their case, helping those in need came from love for one’s neighbor, and not from love of God. The author of the letter to the bishop, Armand Neut, pointed out that the Masons were engaged in charity only for their own benefit.

“We will show with the help of documents provided by Freemasonry itself that in Belgium and France philanthropy does not cover even a thousandth part of what Catholic charity does,” the publicist wrote.

The struggle between pro-Catholic conservatives and Freemasons did not fade away in the 20th century, when the main anti-Masonic theses, popularized by conservatives, formed the basis of the fascist doctrines of the 20th century, which aimed at the widespread destruction of European Freemasonry.

Museum

Museum