Johann August von Starck: German, Latvian and Russian Freemasonry

Some of our latest news

Johann August von Starck: German, Latvian and Russian Freemasonry

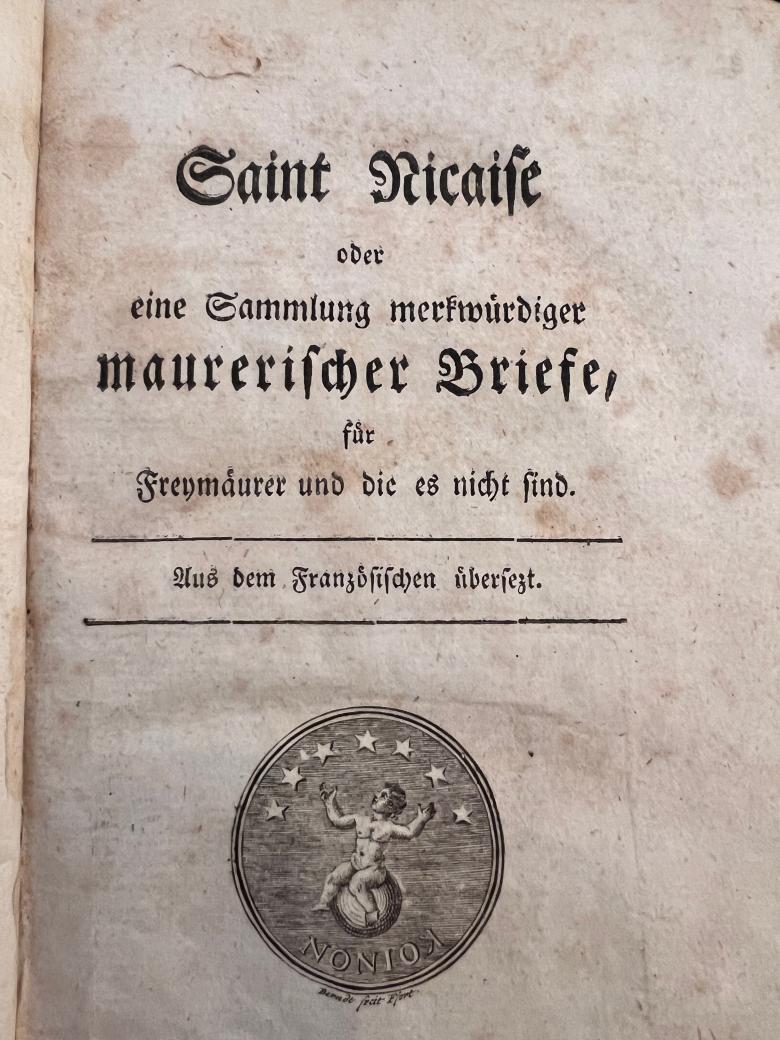

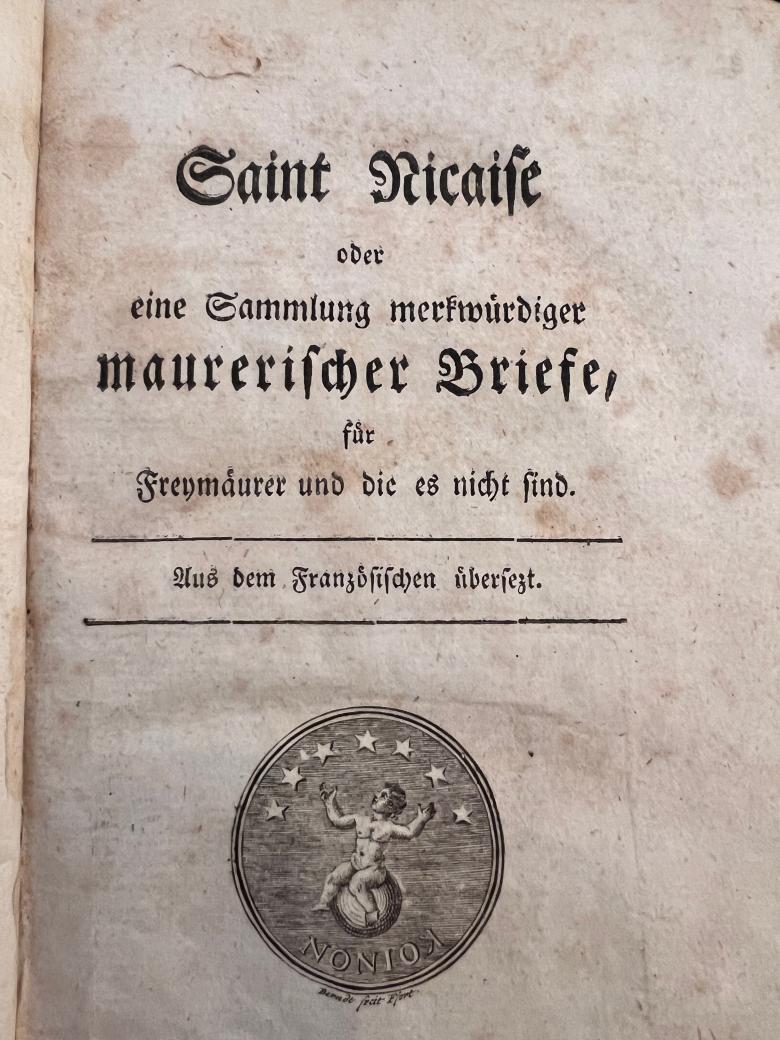

This week's object is the first edition of the book by the famous German educator and Freemason Johann August von Stark (1741-1816) "Saint Nicasius, or a collection of curious Masonic letters for Freemasons and those who are not" (Saint Nicaise oder eine Sammlung merkwürdiger maurerischer Briefe, für Freymäurer und die es nicht sind), published during the author's lifetime, in 1785.

Johann August von Starck was born in 1741 in Schwerin and was the son of a local Lutheran priest. Eager to follow in his father's footsteps, Starck enrolled at the University of Göttingen, where he studied theology and Oriental languages, which later fuelled his interest in the origins of Freemasonry and the study of the Hebrew spiritual heritage in the fraternity. It is important to note that Starck was a student of one of the major 18th century German Orientalists - Johann David Michaelis, from whom he learned in depth the Classical Hebrew language and various theological aspects of the Old Testament.

It is known that during his studies von Starck was admitted to the local Masonic lodge in Göttingen, presumably in 1761. During the same period, he received a job offer and travelled to St. Petersburg, where he taught Oriental Studies and at the same time was the spiritual superior of the local Lutheran community.

The stay in St. Petersburg can be considered fateful for Starck, because it was in this city that he met a noble Russian military leader and Freemason of Greek origin - Peter Melissino (1726-1797). Peter Melissino was a native of the Greek island of Kefalonia and a descendant of one of the oldest Byzantine families, dating back to the nobility of Constantinople in the early 9th century and related to the Byzantine emperors. In St. Petersburg, Melissino was one of the most active Freemasons of his time. He was particularly interested in alchemy and the possible continuity of secret knowledge through ancient Egypt, Greece and Judea into Freemasonry, through the mediation of the Order of Templars.

In the late 1760s, Starck returned to Göttingen, where he helped found a lodge under the Rite of Strict Observance, the essence of which was a commitment to Christianity and the already mentioned version of the more ancient roots of Freemasonry, going back to the Templars, and through them - to the ancient Jews, Greeks and Egyptians. In 1768 Starck, on a Masonic commission, again visited St. Petersburg, after which he went to Königsberg to teach Oriental languages. It is noteworthy that at this particular time Starck was a neighbour and a close companion of the philosopher Immanuel Kant.

While continuing his studies, in 1773 Starck received his doctorate in theology and began to study the influence of Greco-Roman religion, especially the ancient Greek mysteries, on early Christianity. In particular, this concept was the focus of Starck's philosophical work "Hephaistion", published in 1775, which sparked theological controversy in Protestant Europe.

In 1776, Starck received another invitation and moved to Mitau (modern Jelgava, Latvia) to teach philosophy at the Mitau Academic Gymnasium, also known as Academia Petrina. Here Starck lived until 1781 and took an active part in the local Masonic lodges, being a member of the city's main lodge "At the Three Crowned Swords" (Zu den drei Gekrönten Schwerdtern). Also in Mitau, Starck wrote the work "History of the Christian Church of the First Century" (Geschichte der christlichen Kirche des ersten Jahrhunderts), published in 1779.

Contemporaries noted that with age Starck became more conservative, opposing secular trends in Freemasonry and clearly adhering to his thesis about the ancient origin of the brotherhood and its close ties to Christianity. In 1781, Starck left Mitau and went to Darmstadt, where he spent the remaining years of his life.

Gradually drifting away from his former views, Starck criticises the Rite of Strict Observance and its founder, Baron Karl Gotthelf von Hund, accusing him of conspiracy. Starck denies that the Order is governed by some "supreme unknowns", which later turned out to be a fabrication of Baron von Hund.

A book from the collection of the Riga Museum of Freemasonry, "Saint Nicasius, or a collection of curious Masonic letters for Freemasons and those who are not", is devoted to this very topic. In it, Starck criticises the secular French Enlighteners and the Rite of Strict Observance, but does not abandon the theory that Freemasonry inherited ancient wisdom through the mediation of the Templars.

At the same time, Starck began to deny the continuity of Freemasonry and ancient religious cults, pointing only to their mutual ideological influence on the formation of the structure and rituals of the brotherhood. The central thesis of Starck was the idea that there are no ideological contradictions between Freemasonry, Christianity and ancient Greek mysteries and all of the above elements are part of a single spiritual system that contributes to the inner development of man. It should be emphasised that Starck's signature can be found on the document of the Grand Constitutions of 1786, which is the basis of the Rectified Scottish Rite, which actually replaced the Rite of Strict Observance.

During the French Revolution, Starck's views became even more conservative, and he subsequently accused the French Enlightenment philosophers and the Order of the Illuminati (which was in decline at the time) of a vast conspiracy against the French monarchy. This idea was viewed negatively by his contemporaries, and Starck himself was accused of making up conspiracy theories, since he did not point out in his works that the Freemasons in France were on both sides - the revolutionaries and their opponents.

In the early 19th century, Starck continued his polemics with politicised Freemasons, adhering strictly to views, that are close to modern regular Freemasonry, namely that Freemasons should not discuss or interfere in the political and religious sphere.

Johann August von Starck can be considered one of the most interesting Masonic thinkers of the 18th century. It is on the example of his life path that one can clearly see the metamorphosis of Freemasonry in the second half of the 18th century, the evolution of various Masonic systems and the intellectual rivalry in the minds of the representatives of the Age of Enlightenment.

Museum

Museum