Plato, Neoplatonism, and Freemasonry

Some of our latest news

Plato, Neoplatonism, and Freemasonry

It's believed that Freemasonry is exclusively elite, secretive, anti-religious (especially anti-Christian), often even equated with the mafia. But is this really the case? We'll try to debunk these myths and describe one of the foundations of Masonic philosophy - Neoplatonism. It will become clear that Masonic ideas are not contrary to Christianity, but share common roots with it.

To understand the origins of Masonic philosophy, we must start with the most famous ancient philosopher - Plato. History preserves works that are timeless. Plato is the only ancient philosopher whose works have come down to us in full.

Geometry plays a crucial role in Masonic allegories, and this is no accident. Plato first said in the "Meno" dialogue that knowledge of the truth is possible through geometry and mathematics. Therefore, an exam in geometry was a requirement for admission to Plato's Academy, because algebra and geometry prove the existence of absolute truths, including objective aspects of morality and ethics. Here, we see a clear connection to Freemasonry, where the goal is to work with the rough stone, i.e., moral and ethical self-improvement.

Plato's ideas were further developed, influencing, for example, Stoicism. By the 3rd century, the evolution of ancient thought led to Neoplatonism. The actual founder of Neoplatonism was the outstanding philosopher Plotinus, born in Egypt in 204, who established the main ideas of this philosophical school. Plotinus's main idea - union with the divine, which is infinite and transcendent. Plotinus's system essentially takes the idea of the infinity of the deity to the extreme, suggesting that the first cause is without any boundaries and cannot be ascribed bodily and spiritual qualities. In turn, matter is seen as a shadow of the true metaphysical world, but Plotinus rejects the Gnostics' contempt for matter and believes the physical world is as beautiful as possible for the material world. According to his teaching, the main task of the soul is to strive as much as possible for the metaphysical world and get rid of the shackles of passions. In the context of Freemasonry, Plotinus's concept of deity effectively provides a basis for tolerant attitudes towards people of different religions and denominations, creating an adaptable form that each person can fill with their spiritual views without contradicting Masonic philosophy, ethics, and morality.

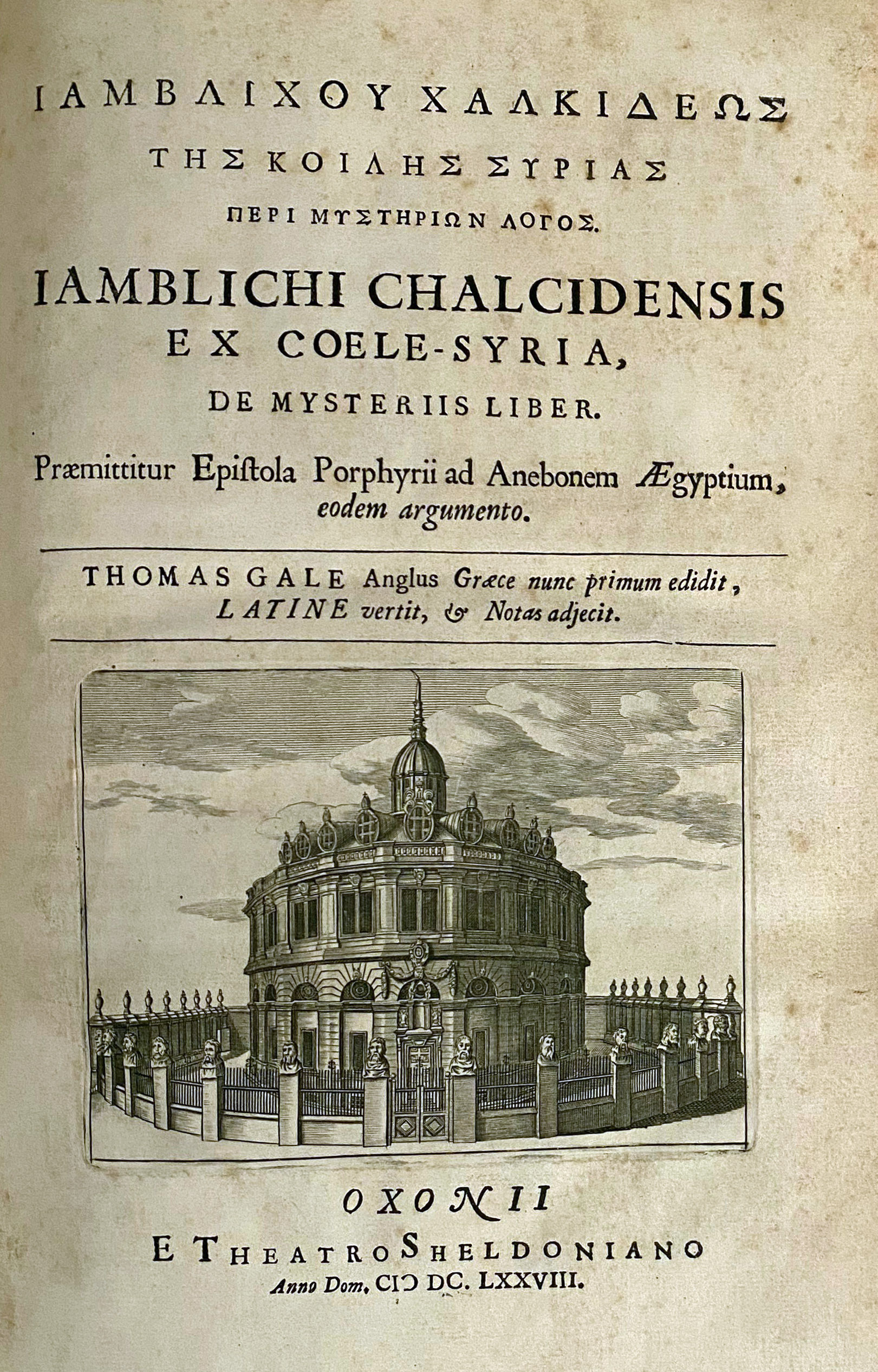

The second significant figure in Neoplatonism is Iamblichus, a great ancient philosopher from Syria, who continued to develop Plotinus's ideas. Since Iamblichus spent his life in Syria, he was greatly influenced by Eastern philosophy. Under its influence, Iamblichus mythically interpreted the following Neoplatonic ideas: for example, he acknowledged a primordial deity that divided into a Trinity and then multiplied into numerous gods, reaching 360 gods. Acknowledging the eternity of the world, Iamblichus also highlights fate - a force that rules over man and from which one can only be freed thanks to the intervention of the gods. In the "On Mysteries," likely written by Iamblichus or one of his closest disciples, theurgy is described - a form of magic involving various ritual practices to influence the deities. Therefore, Iamblichus logically concludes the corpus of Neoplatonic thought, creating a starting point for subsequent centuries when these concepts influenced thinkers and alchemists of the Renaissance. Subsequently, the basic concepts of theurgy and the necessity of rituals laid the foundation for modern Freemasonry.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, a huge number of philosophical works were lost, and scholasticism - a theological system based on the works of Aristotle, Plato's disciple, which was based on dogmatic legalism - gradually strengthened in the Western church tradition. In turn, the Eastern Roman Empire, later called Byzantium, preserved most of the ancient texts until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The unbroken connection with antiquity influenced Eastern Christianity, so modern researchers rightly believe that the blood of ancient mysteries flows in the veins of modern Eastern Christianity, and Plato's philosophy plays a noticeable role in it.

As the Arab and Ottoman conquests and the fall of Byzantium progressed, the Islamic world adopted Greek texts, as medieval Arab writers write. As for the Byzantine Greek-speaking intelligentsia, in the 14th and 15th centuries, most Byzantines fled Ottoman conquests, emigrating to Italy.

One of the most influential Byzantine thinkers was Georgius Gemistus Pletho, who arrived in Florence from Constantinople in the first half of the 15th century to help reconcile differences between Catholic and Orthodox clergy. Pletho began actively promoting the works of Plato and Neoplatonic philosophers in the Florentine Republic, particularly noting the kinship between Christian theology and the Platonic school in his lectures, and criticizing medieval scholasticism and Aristotle's teachings.

In his treatises, Pletho insisted on the necessity of developing morality and ethics based on Neoplatonism and proposed reforming Western theology by completely abandoning dogmatic scholasticism, replacing it with authentic philosophical works of antiquity. For example, describing theology, Pletho emphasized that the Universe is eternal and, following the principles of logic, is not created by God but is in eternal unity with Him.

After Georgius Gemistus Pletho lectured on ancient Greek philosophy at the University of Florence, the famous politician and philanthropist Cosimo de' Medici began funding humanists who studied the works of Plato and Neoplatonists in the 1440s. As a result, in 1459, the Platonic Academy was founded in the Medici-owned Villa Careggi, gathering leading Renaissance humanists who collected, commented on, and translated Plato's and Neoplatonists' works into Latin. During the Platonic Academy's existence until the 1490s, a series of lectures on the culture, aesthetics, and philosophy of Ancient Greece was delivered, thus creating the basis for Renaissance Neoplatonism.

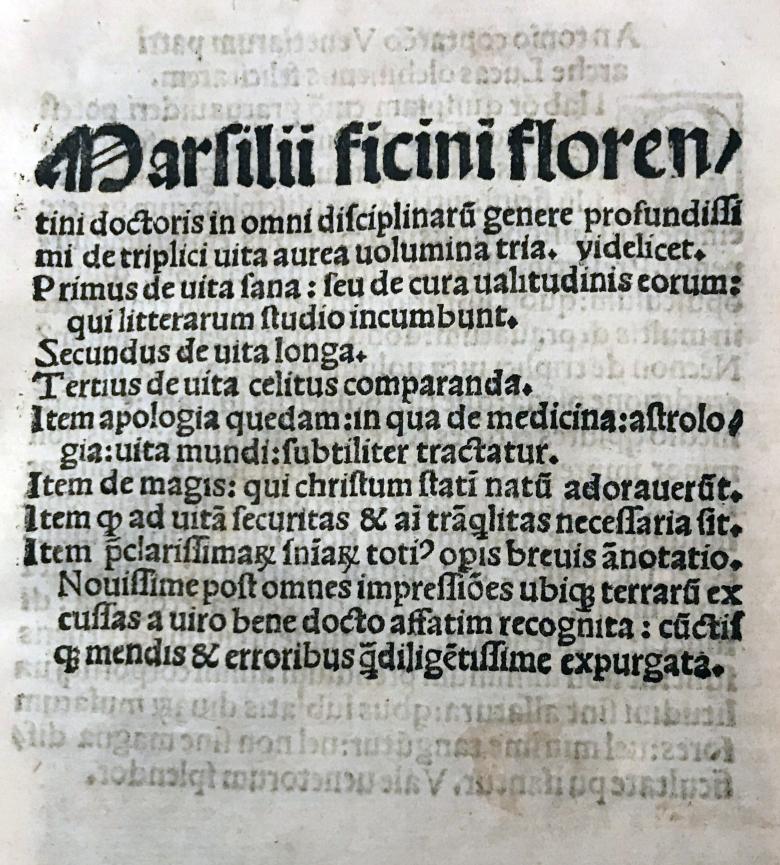

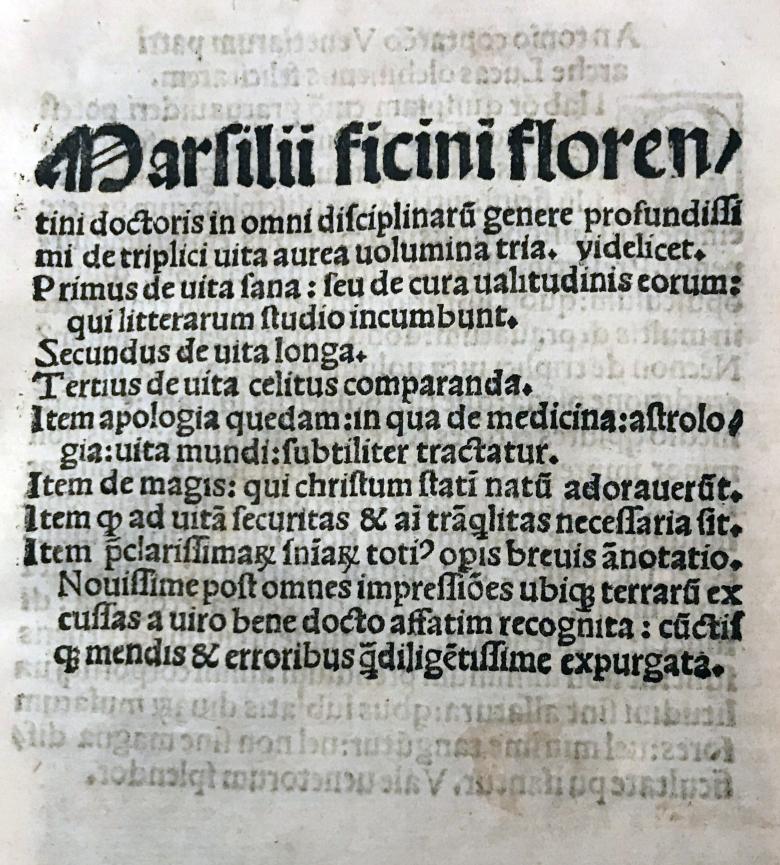

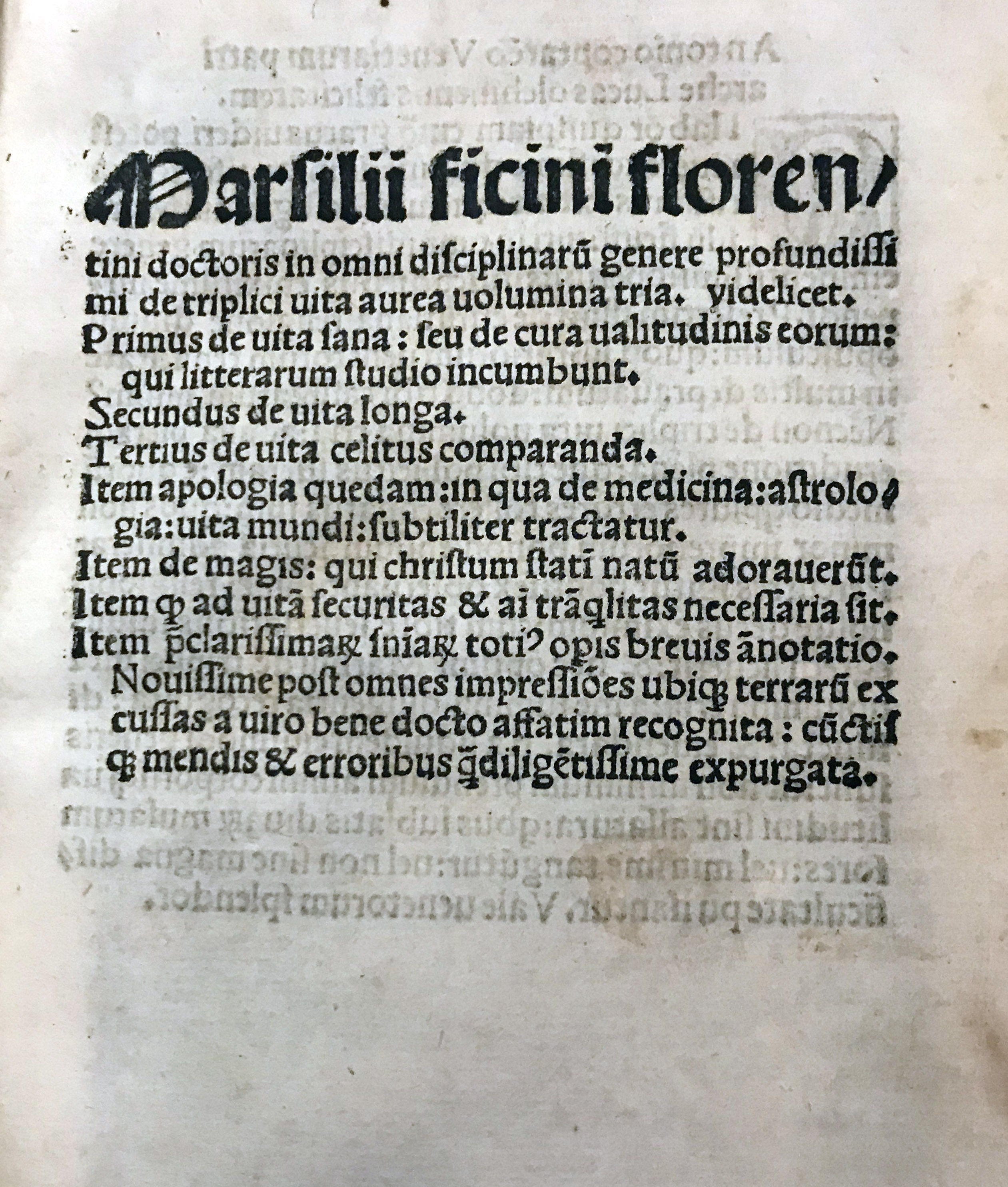

The driving force of the Platonic Academy and its actual leader became the Florentine humanist and theologian Marsilio Ficino, whose family had close ties with the Medici dynasty. During his studies at the University of Florence in the mid-15th century, Ficino attended Georgius Pletho's lectures, awakening a deep interest in ancient philosophy and the Greek language in him. In 1462, Cosimo de' Medici appointed Ficino head of the Platonic Academy in Careggi and handed him all of Plato's works in Greek. Becoming the leading Florentine philosopher and linguist, Ficino translated all of Plato's works from Greek into Latin in the 1460s, as well as the works of major Neoplatonism representatives, such as Plotinus, Porphyry, and Iamblichus.

In his treatises, Ficino, like his teacher Georgius Pletho, considered Plato the greatest thinker. Using Platonic allegories, Ficino justified the existence of universal metaphysical principles and God using the thesis about the source of all movement. In other words, if everything in the Universe, including reason and soul, is in motion, then movement must have a source - God. Essentially, this logical formula corresponds to the Masonic concept of the Great Architect of the Universe. Ficino also used Plato's concept of the correspondence between the microcosm and macrocosm, according to which the human mind is a reflection of the Universe, and each individual can find patterns with the spiritual world. Here again, we see a key aspect of Freemasonry - constant and meticulous moral and ethical work on oneself, which, in a broad perspective, contributes to improving society as a whole. Regarding the structure of the Universe, Ficino considered it hierarchical, with man between matter and the metaphysical world, striving to achieve harmony between these two spheres. Here again, we see an analogy with Freemasonry, namely - strict mathematical hierarchy, which, in essence, reflects both the inner world of man and the Universe.

Organically evolving, Plato's philosophy was enriched and perfected, becoming in the Renaissance the starting point from which speculative Masonic philosophical thought subsequently grew.

Illustrations from the museum's collection:

Title page of "Three Books on the Life” by Marsilio Ficino, Venice, 1517;

Title page of the edition "The Mysteries of Egypt" by Iamblichus, London, 1678

Museum

Museum